Vibe coding is this emerging way of building applications and systems where you sketch with words and screenshots instead of writing code.

And that shift changes the role of the designer—suddenly, the tool is less about commands and more about conversation. Which brings me to my first encounter with Lovable.

When I first sat down with Lovable, I didn’t think I was learning a new tool.

I thought I was confronting a mirror. Here’s this platform that promises to build an app from natural language, but what it really does is hold up a reflection of my own clarity.

I decided to put it to the test with something that had enough complexity to expose its seams: a cat café app.

A place where people could browse cats, book sessions, sign waivers, maybe buy a latte. It’s whimsical, but it has real rules. And there’s no better way to stress test an AI co‑developer than to throw kittens and liability into the mix :)

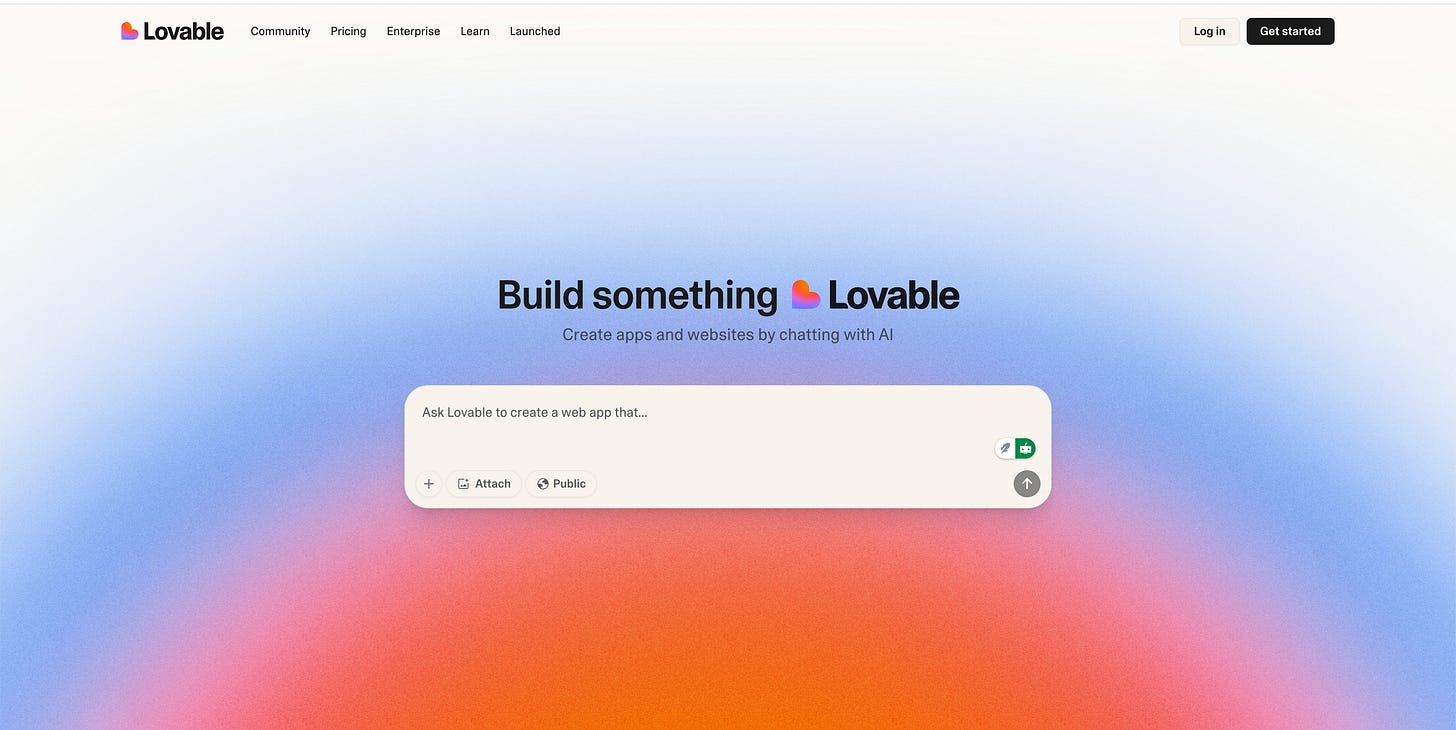

The first prompt I gave Lovable was almost embarrassingly vague: “Create a Cat Café app with Home, Cats and Booking pages.”

It obliged, and the result wasn’t bad at all, but it felt a bit raw. No personality, no rules, no charm.

And that’s where the first reflection hit me:

Lovable will always mirror the specificity you give it.

If you say “something tasty,” you get a plain latte. If you say “an oat‑milk cappuccino with one pump of vanilla,” that’s what you get.

In UX terms, prompting is design.

It’s our responsibility to articulate the experience clearly, not just the components.

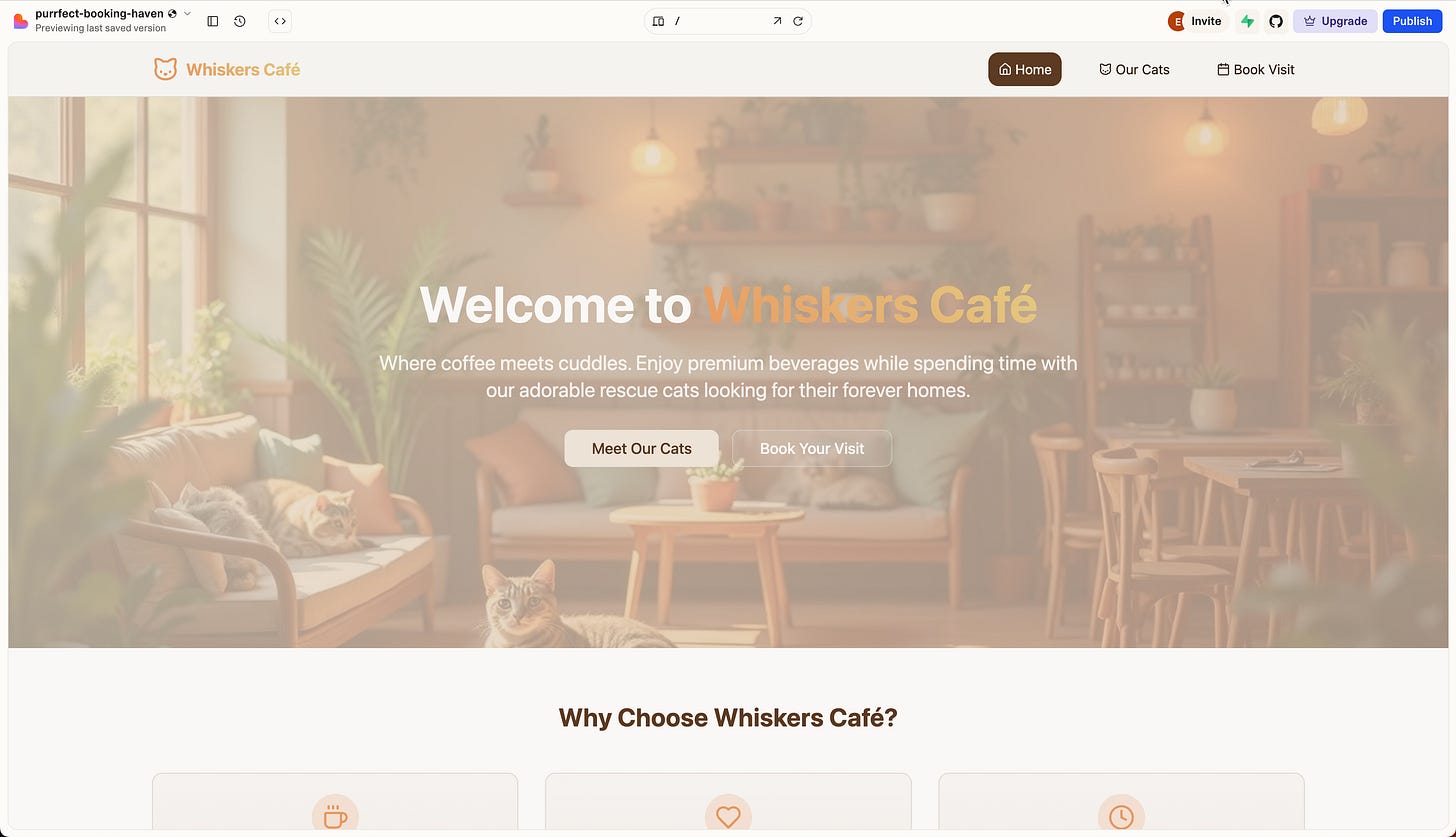

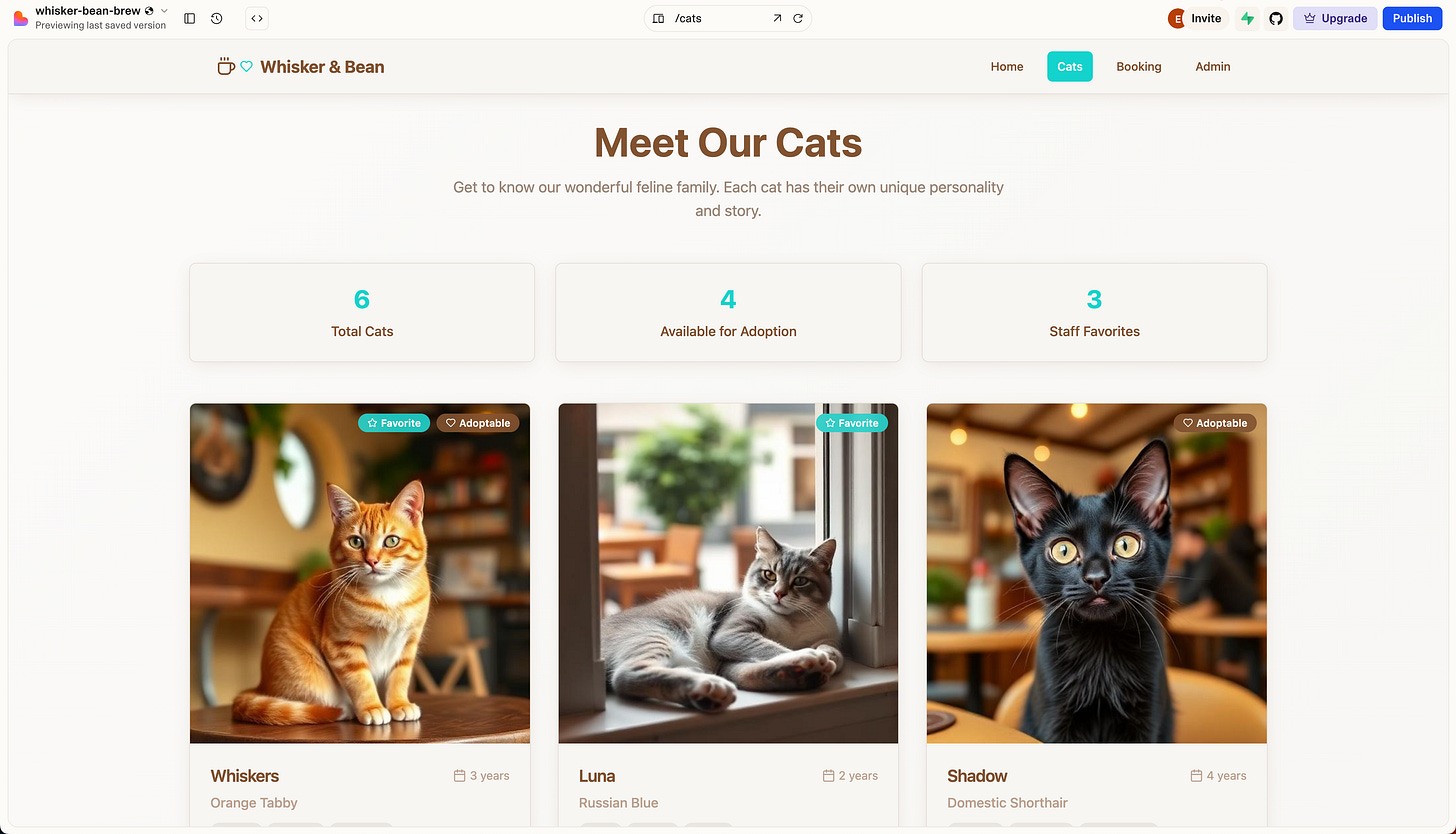

So I got specific. I broke my desires into structure: an overview (“A Cat Café app where guests book sessions to play with cats”), a list of pages and what each should do (“Home introduces the café, Cats shows profiles with photos and temperaments, Booking lets you pick a date and time”), and even database requirements (“cats, bookings, users”). I mentioned the tone and colours—cream backgrounds, coffee browns, a touch of teal. This was no longer a wish. It was a spec in sentence form.

The difference was dramatic. The Cats page now had placeholders for real cats. The Booking page had a date picker and a semblance of flow.

It wasn’t perfect, but it felt like a café app instead of a generic booking tool.

And I realised that my job was shifting from pushing pixels to communicating intent.

The clearer I was, the closer Lovable’s draft was to my mental model.

But here’s where things got interesting. Once the first draft appeared, the game became about refinement.

Clicking “Book Now” took me to a dead end.

The “Meet the Cats” link did nothing.

The layout felt bland. In a traditional project, I’d open a code editor or ping a developer.

In Lovable, I started to treat the platform like a junior designer. I gave feedback in context.

“When I click the ‘Book Now’ button, it goes to a 404 page. Please link it to the Booking page.” Immediately, the button worked. “On the Cats page, show a grid of photos with names and tags.” Lovable restructured the page.

I didn’t say “fix it”; I explained what was wrong and what outcome I wanted.

Sometimes words weren’t enough.

I wanted the cat cards to have a certain look—photo on top, name below, temperament tags in little chips—and the AI’s interpretation was off.

Rather than typing a verbose description of spacing and typography, I spent two minutes in Figma drawing boxes and text.

I took a screenshot, uploaded it into Lovable, and said, “Match this layout.”

This simple image—just rectangles and placeholder text—did more than paragraphs could.

Another pro tip: you can sketch things on a piece of paper, feed it to ChatGPT, and then take a screenshot of your desired design and feed it to Lovable.

This interplay between text and visuals became my new workflow.

Figma wasn’t a deliverable so much as a conversation partner. I sketched ideas, took screenshots, and used them as visual evidence in my prompts.

This multimodal dialogue is something UX has done forever—verbal critique coupled with sketches—but it’s now happening with a machine.

It’s collaborative, iterative and strangely personal.

Usability tests conducted by the AI

It’s worth emphasizing again that not everything went smoothly. Errors were constant companions. So don’t give up soon!

Sometimes I would click an upload button and nothing happened. Sometimes the system would allow more guests than it should.

Instead of seeing these errors as failures, I started to see them as usability tests conducted by the AI.

When a slot overbooked, it meant I hadn’t told Lovable the capacity rule. When a form didn’t submit, it meant I hadn’t specified the database table or the connection.

Each error forced me to reflect on the gap between what I thought I said and what I actually wrote.

The strategy became clear: describe the problem, provide any evidence (like copying a console error or uploading a screenshot of a blank state), and ask for the desired outcome.

For example, “When I try to upload a video into the gallery section of the app, the console says Cannot read properties of null (reading reset). Please fix this.”

Lovable would then generate a small patch, update the code, and ask me to apply it.

To be honest, it felt like debugging, but it was also like teaching.

The AI didn’t know what it couldn’t see; I had to point it out.

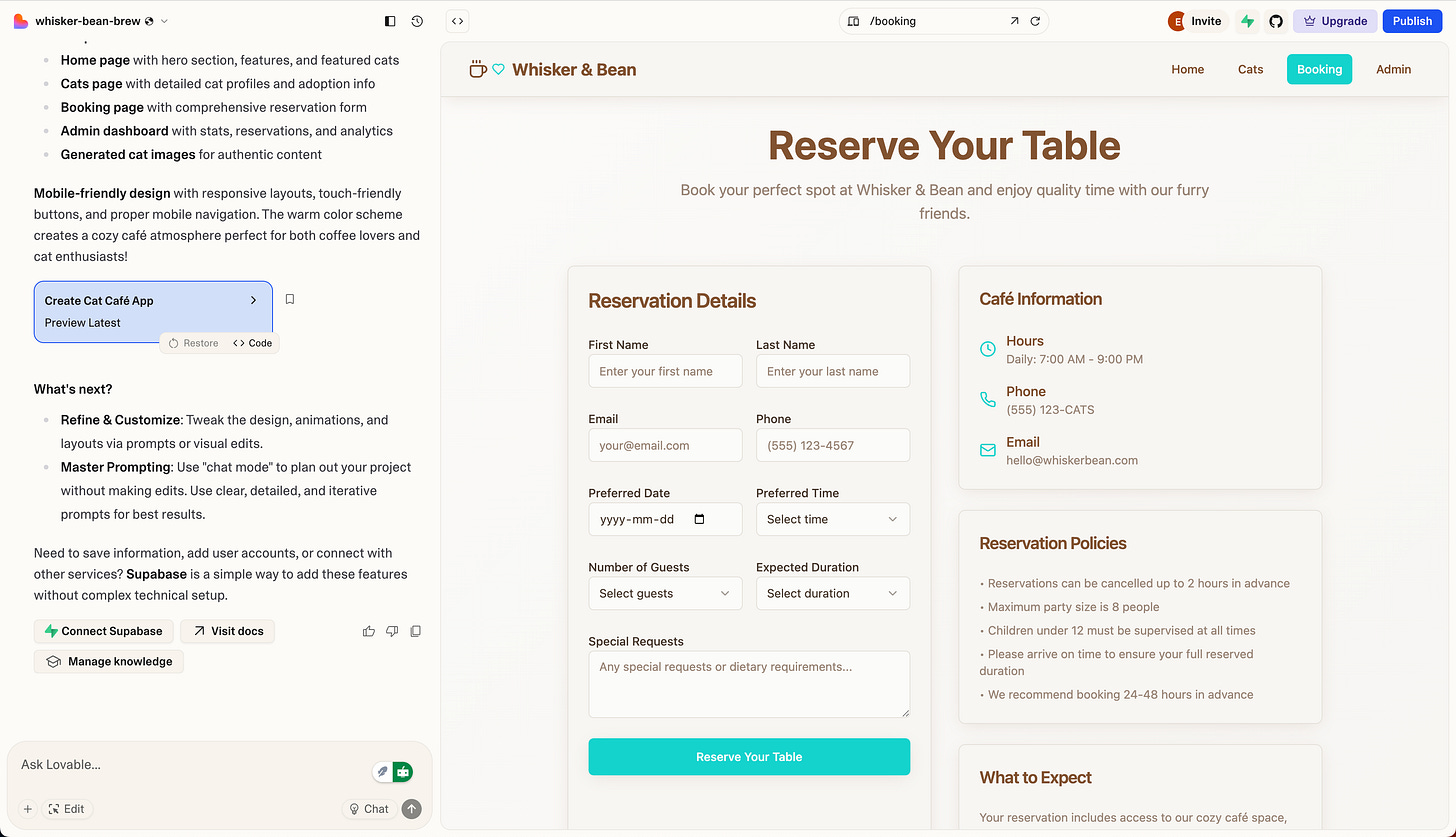

The biggest shift happened when I connected the app to Supabase. Supabase is an open-source platform that provides backend services (e.g., database) for web and mobile applications, and it integrates seamlessly with Lovable.

Up until then, every change was cosmetic.

I could refresh the page and lose all bookings.

To make the café real, I needed persistence.

So, after making the connection with Supabase, I told Lovable to create a cats table with specific fields and a bookings table for session reservations.

Lovable built the schema and wired the forms.

The first time I booked a session after connecting the database, I felt super satisfied: I refreshed the page, and my booking was still there.

Data turns prototypes into products. It’s not just a technical layer; it’s the spine of the experience.

Once data existed, we could do more. Waivers needed to be stored per guest. The admin needed to see a schedule with capacity counts. People needed to log in and see their bookings.

Each of these was a new conversation with the AI: “Create a waiver_signatures table and prevent check‑in unless all guests have signed.” “Add a protected Admin page that shows a table of bookings by date with a cancel button.” “Limit users to two active bookings per day.”

Each requirement moved us further from a toy app and closer to a system that could run a small business!

Publishing came last.

I clicked Lovable’s Publish button, waited a minute, and out came a URL.

Suddenly, this thing we had been building lived on the web.

I shared it with a friend; they booked a cat session and their reservation appeared in my admin dashboard. It felt surreal.

However, you need to be cautious here:

Publishing means you’re accountable. Live data, real users, potential legal implications.

Lovable makes it easy, but the ethical and practical responsibilities remain.

As the designer, you’re still responsible for accessibility, for privacy, for making sure the café’s policies are clear.

What did I learn?

In the final moments, I stepped back and considered what I’d learned.

Working with Lovable is like holding a mirror to your design thinking. It forces you to articulate your intentions with words and pictures.

It shows you the consequences of vague requirements. It turns errors into reflection points. It collapses the gap between idea and implementation, but it doesn’t remove the need for human judgment. If anything, it amplifies it. You become the storyteller, the critic and the coach all at once.

Looking ahead, I strongly believe that tools like Lovable won’t make UX designers obsolete. They will change our focus. We will spend less time on manual labour and more time on clarity, ethics and human insight.

The skills that will matter most are the ones that have always mattered: understanding people, telling stories, recognising nuance, and making decisions with care.

The interface between human and machine is now a conversation. And our job is to make that conversation meaningful.